FORTIFY

April 21, 2025- Shonelle was fearless as she navigated the narrow winding road at various speeds, reserving one hand to grip the steering wheel of a compact sedan and the other to give her newly arrived passengers a rundown of the story behind whatever surrounded us.

My wild curls were frizzing, the strands swollen by the island heat as I hung out of Shonelle’s backseat window. Inhaling the sweet scent of sugar cane residue in the air, I focused my eyes on the neat sequences of towering plants. They dotted the perimeter of what seemed to be endless fields and swayed in the wind as we listened to the melody of Shonelle’s voice, her alto punctuated by a thick Bajan accent. Our driver took great pride in connecting the dots between nature, ancestral spirits and Black survival.

“Ya see di palm trees, yeah?” Shonelle asked us. “The slaves planted dem to guide demselves when di moonlight was not enough.”

Shonelle was the witty woman in charge of escorting our collection of Black women writers from the Barbados airport in Christ Church parish to the serene shores of Bathsheba, a quaint fishing village in St. Joseph. It was home to our Island Scribe writing retreat, a literary movement birthed by Trinidadian-born writer, mentor and educator Simone Dalton.

Our route to a writers’ paradise wound through sugar cane plantations of centuries past and in some cases, economic futures. They’re all visual reminders of how closely we interact with history each day.

Despite it being the thirteenth smallest nation in the world, Barbados is home to more than 600 former plantations. Some carry subtle to no reminders of the West Africans and their descendants who were forced into bondage, comprising 80 percent of the island population and 100 percent of the hard labor workforce resulting from the Transatlantic slave trade. Other plantation sites are modern day tourism hubs, nodding to the legacy of enslavement so often aligned with American history.

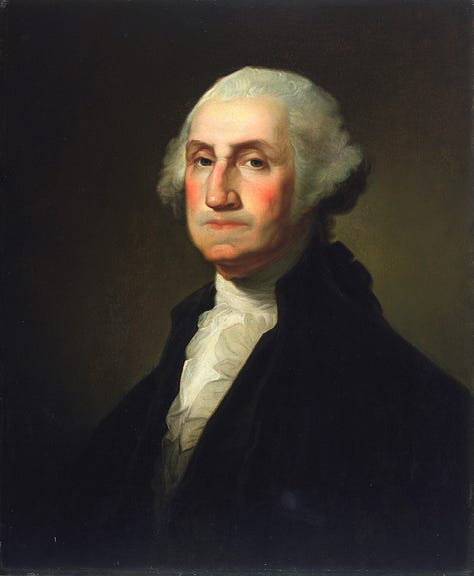

More than three decades before he was a Founding Father or President the United States, George Washington made his first and last international voyage, landing in Barbados with his half-brother Lawrence.1 The yellow colonial home the pair shared from 1751-1752 is now a part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site in historic Bridgetown and its Garrison. Inside the museum, visitors will find artifacts that bring some of the horrors of enslavement to life, including shackles, barbed neck wire and chains.

The young Washington returned to the continental U.S. after his brief stint in Barbados, where he’d studied the British Empire’s economic and security vulnerabilities. Washington’s own writings show the divide between his moral conscience, views on democracy and thirst for economic gain through his slaveholding. Later in life, his Founding Father virtues were challenged by Edward Rushton, an abolitionist from Liverpool who turned into a human rights activist after working as a sailor aboard a slave ship that embarked upon the Caribbean nations.

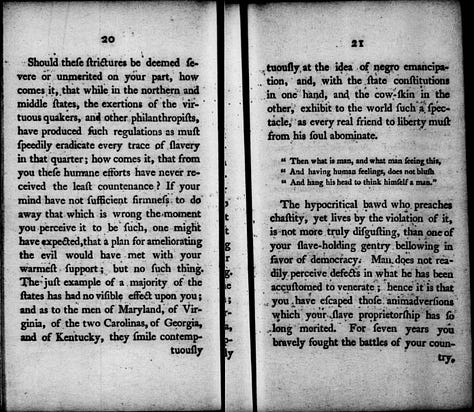

In part of the 1797 letter he wrote to Washington, Rushton pointed towards the American leader’s hypocrisy :

“If your mind have not sufficient firmness: to do away that which is wrong the moment you perceive it to be such, one might have expected, that a plan for ameliorating the evil would have met with your warmest support; but no such thing,” Rushton wrote to Washington. “The just example of a majority of the states has had no visible effect upon you; and as to the men of Maryland, of Virginia, of the two Carolinas, of Georgia, and of Kentucky, they smile contemptuously at the idea of negro emancipation, and, with the state constitutions in one hand, and the cow-skin' in the other, exhibit to the world such à spetacle; as every real friend to liberty must from his foul abominate.”2

Another notable Barbados plantation site is Drax Hall, home to the oldest Jacobean mansion in the Western Hemisphere and owned by heir and former member of parliament, Richard Drax. Drax is a conservative politician and until 2024, was the wealthiest landowner in the House of Commons. He also identifies as a journalist.

Former Miami Herald journalist, filmmaker and New America Fellow Jason Fitzroy Jeffers grew up near Drax Hall. Jeffers, a Black Barbadian, is working on a film tentatively entitled The First Plantation. The film description notes Drax Hall was “ built within the British colonial experiment that created the Barbados Slave Code of 1661. This served as the first legal justification for slavery in the New World and the foundation for slave codes across the American South.” Jeffers zeros in on race, capitalism and history as he explores “the intensifying fight for reparations in Barbados, once home to the world’s first slavery-based economy, and the impact of this little-known history on the wider Americas.” You can read more about the project here.

I’m always intrigued by how we reckon with, remember , and transform space. Anyone who has taken one of my journalism classes or perhaps borrowed a book from me knows that I’ll whip out a copy of Clint Smith’s How the Word is Passed to demonstrate the power of public memory, denial and reclamation.

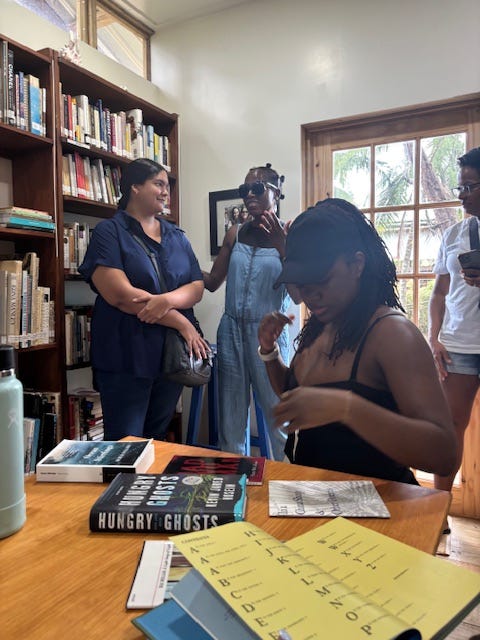

So I was particularly interested in a stop that Dalton chose to enhance our creative journey. Tucked away in the St. George parish is Fresh Milk, an artists’ incubator on the grounds of a late 17th Century sugar cane plantation-turned modern dairy farm.

Fresh Milk was founded in 2011 by Annalee Davis, a white Bajan woman who has written about the social apartheid in which she was reared.3 . Davis, a historian in her own right, has curated a support system for Caribbean artists that includes funding, fellowship and futurism. The dairy farm itself is operated by her brother.

During our visit to the property, we had a chance to sit in the quaint reading room named in honor of Davis’s friend Colleen Lewis. Lewis, a Canadian-born artist who died in Barbados nearly two decades ago, was an avid book collector. From ceiling to floor you can find rare and unique books, many of which came from Lewis’s personal collection. Our scribes each found work that spoke to them, mine being a history of the Black press through the lens of Caribbean journalists.

With philanthropic support, including handsome funds from the Mellon Foundation, Fresh Milk re-grants money to Caribbean artists. Many of them are Black and Brown. Micro-residencies and cross-cultural collaborations between Caribbean nations afford artists time and space to create the work that speaks to our current condition and our histories.

While engaging in this work, Davis confronts the land on which she experienced that social apartheid and benefited from being considered white, despite her mixed-race ancestry.

“Fresh Milk acknowledges the inhumane atrocities that occurred throughout the 400 years of slavery, as well as the lasting impacts of colonization that Barbados and the Caribbean continue to reckon with in present day,” its website reads.

Last year, journalist Janell Ross traveled to Barbados to remind us that the discussion surrounding reckoning and reparations is not new. She notes 17th century court cases filed by the enslaved in a fight for their freedom, and the piece, which you can read here, forces us to face the realities of what repair looks and feels like beyond acknowledgement of atrocities.

Money is owed, no doubt. But what else is owed? Is transforming space enough? Is re-writing the wrongs of revisionists enough? Is anything enough and when will offering nothing be intolerable?

During our Island Scribe retreats, I think about the process of writing as a form of reparative work. It is a process by which we engage in truth-telling, whether it be in the form of non-fiction, poetry or fictional characters who very much navigate the realities of our current existence. This month and in conversation with the renowned Barbadian writer Karen Lord, we explored the themes I’m adamant about centering in my own journey— ancestral guidance, historical preservation and reckoning. The latter seems to be the most challenging.

When my forthcoming book is released next year, you will recognize a theme that goes along with what I pondered in Barbados —the parallels between Black American and Afro-Caribbean histories, intricately woven together by the Transatlantic slave trade and guided by my own ancestor-a Jamaican man, educated in the United States and in the U.K. who fought for freedom under the British Empire only to face racism and resistance in each land he navigated throughout his short life.

This trip was fruitful in many ways, and it’s led me to continue raising a few questions- Who are the narrators of our histories? Which hands open the pocketbooks to tell such histories? And how do we fortify ourselves to depict our ancestors’ stories while preserving the must-tell stories of the moment? Finally, what does meaningful repair really look like?

Washington’s journey to Barbados. George Washington’s Mount Vernon. (n.d.). https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/washingtons-youth/journey-to-barbados

Expostulatory letter to George Washington, of Mount Vernon, in Virginia, on his continuing to be a proprietor of slaves. By Edward Rushton. 1797 : Rushton, Edward : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Annalee Davis. (2020, September 3). On race and whiteness from the context of Barbados #1. https://annaleedavis.com/archive/wk2k8c4s3utm308ljk6h7a17ei6s83

Share this post