FORTIFY

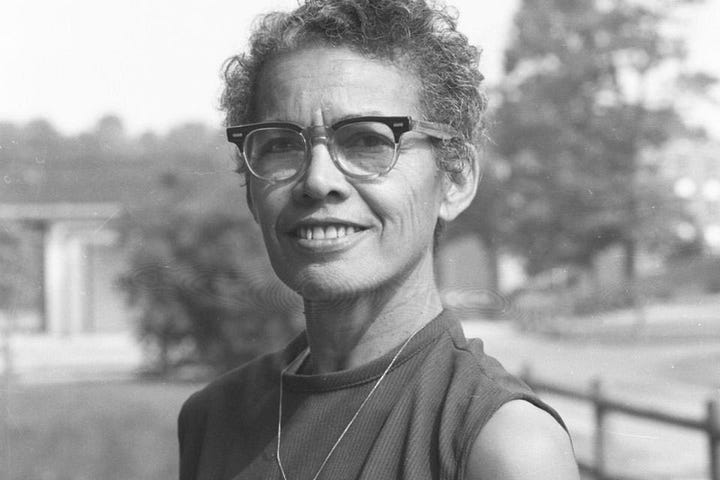

March 10, 2025- To say that the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray was ahead of her time -or any time, really-would be the understatement of the 20th century through which she blazed trails that we don’t get to explore in our school textbooks.

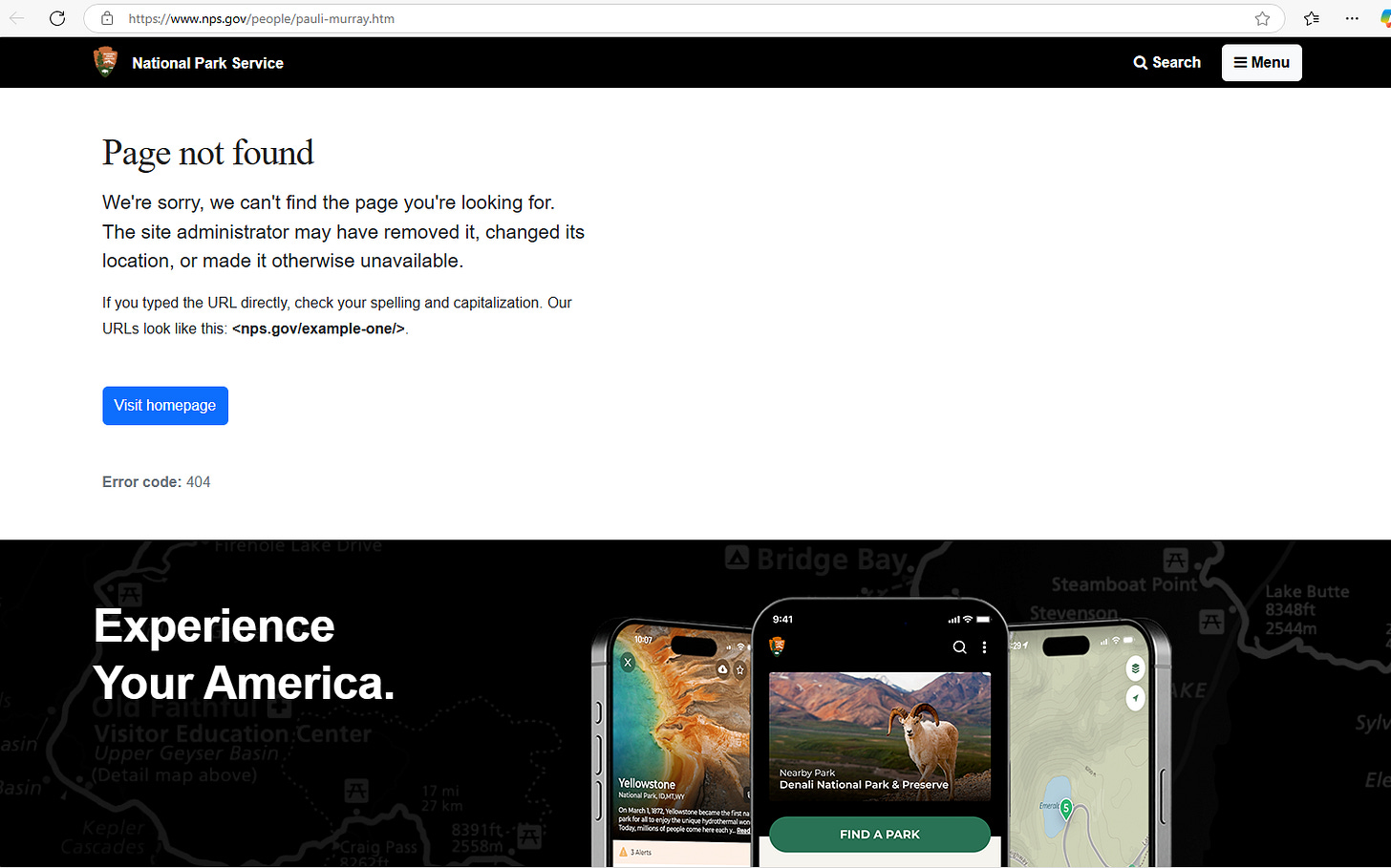

Today, under the Trump Administration’s assault on diversity, equity and inclusion, Murray’s legacy as a Black queer woman and mastermind behind unpacking the problem of “Jane Crow” in America, has been scrubbed from the National Park Service website. This is on the heels of Black History Month and during Women’s History Month, no less.

We’ll get down to that scrubbing in a moment but first let’s explore just a sliver of Murray’s contributions to the years ahead of, during and beyond the civil rights movement.

There would be no Brown v. Board of Education case before the Supreme Court, and certainly no victory without Murray. Murray’s own experiences with university admissions rejection in the 1930s and subsequent law school arguments, influenced Thurgood Marshall’s legal strategy in Brown, although she was not immediately credited for that gargantuan contribution.

As the story goes, then- University of North Carolina president Franklin Graham rejected Murray’s 1938 admissions application into graduate school , writing in a letter that “members of your race are not admitted.”

Now the plot twist in this story is the fact that Murray herself, a woman born in 1910, was a descendant of the white family that bequeathed land to build the University of North Carolina.1 Ellen Tucker’s 2022 TeachingAmericanHistory.org blog, describes how Murray hoped that a landmark case-Missouri v. Gaines-would change the course of her educational journey. It made sense shortly after her UNC rejection, since the Supreme Court determined that because there was no Negro law school for an applicant named Lloyd Gaines to attend, the state’s White institution had to admit him.

She even bucked against Graham in a letter challenging his decision. I leaned on the historic Black press to parse out the details and found a 1939 California Eagle article that republished Murray’s questions for Graham and the student body:

“If the students of the University of North Carolina are convinced that it is unjust, unwise and dictatorial to admit a Negro student into their classes, by what means can they test this theory in real life if they have not had the experience of a Negro student on the campus?” Murray wrote.2

While the “separate but unequal” argument worked for Gaines, it did not cause the brass at UNC to budge on their decision as they deflected to a states’ rights mantra to justify their discrimination against Murray and other Black students. Graham claimed he’d need the blessings of state lawmakers to admit them.

So Murray went on to study law at Howard University, the historically Black and federally-funded institution in Washington, D.C. At Howard, Murray began crafting arguments around the concept of “separate but unequal,” as a way to break through the Plessy arguments and challenge the constitutionality of segregation. She graduated first in her class and this work was expanded in her ACLU-funded pamphlet to study women’s rights and discrimination (by the way, it’s important to note that following the Howard graduation, Murray was denied admission into Harvard because she was a woman). Marshall circulated the sum of Murray’s work around the NAACP Legal Defense Fund to prepare for Brown.

In her book Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage (posthumously published in 1987) Murray recounts the day her Howard University professor revealed that her work had been the bedrock of the Brown strategy. It was nearly a decade after the legal victory.

Tucker’s blog cites an excerpt from the memoir.

“. . . he casually mentioned that when he had left the law school to go into private practice, he had taken my paper with him. He had not thought much of it when he first read it . . . but in 1953, when the NAACP legal defense team was preparing arguments for Brown v. Board of Education, he took another look at it and thought better. ‘In fact,’ he went on, ‘it was helpful to us. We were able to use your paper in the Brown briefs . . . .’ Thinking of all the years that had passed without my knowing that my work had not been wasted effort, all I could say was, ‘Spots, why on earth didn’t you tell me?’”

Beyond being the first to solidify the Brown strategy, Murray was a pioneer of the civil rights movement and a cultural force who was not fully appreciated during her time Earthside.

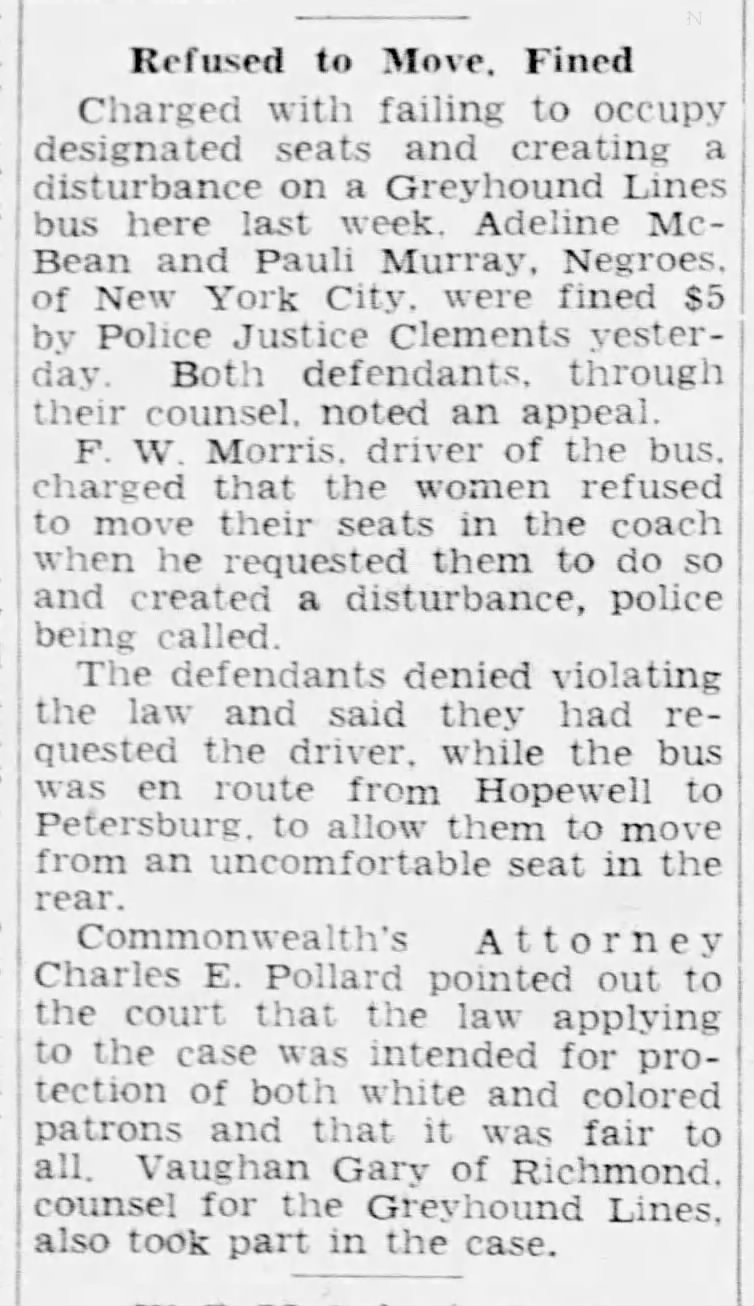

In 1940, Murray and another Black woman named Adeline McBean refused to get out of their coach Greyhound bus seats and move to the back of the bus. I pulled the clip above from a March 1940 edition of the Richmond Times-Dispatch.3 It describes the ordeal that took place on the bus line between Hopewell and Petersburg, Virginia. Murray and McBean appealed their charges and fines, but it’s important to note that this went down a full 15 years before Claudette Colvin’s and Rosa Parks’s Montgomery arrests for refusing to give up their bus seats.

Two decades before the young men known as the Greensboro Four sat-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter, Murray’s Washington, D.C. sit-in forced a local restaurant to desegregate.

Thirteen years after educator, journalist, suffragist and civil rights activist Ida B. Wells co-founded (and was largely uncredited for the founding of) the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , it was Murray who spearheaded the founding NOW-the National Organization for Women. She proposed the co-founders operate the multiracial coalition for women’s rights in the spirit of the NAACP.4

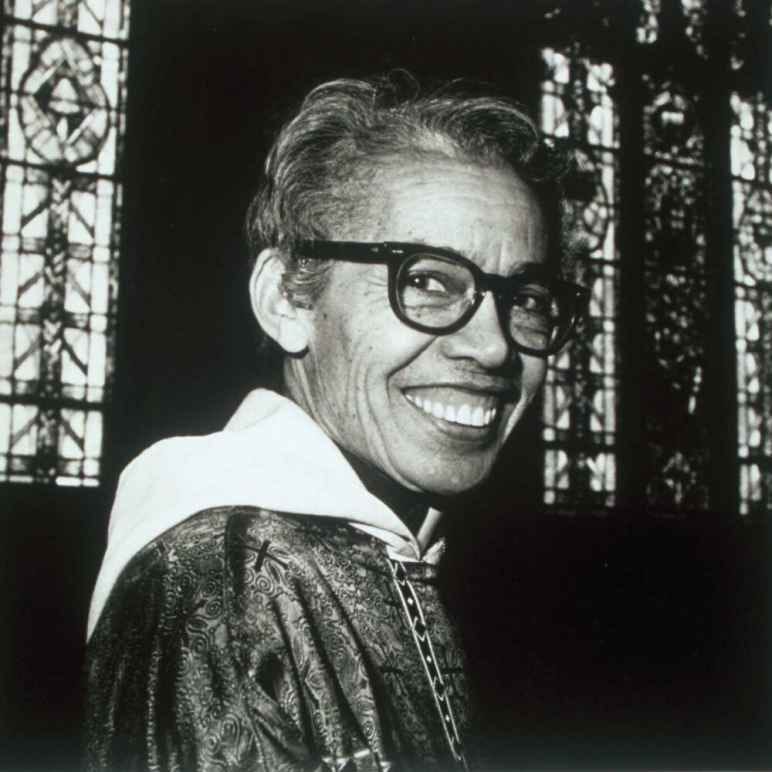

Murray was the first Black person to earn a Doctor of the Science of Law degree, or J.S.D., from Yale.5 And in 1977, Murray became the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.6

You would think that Murray’s story would be widely known to schoolchildren and adults alike, although that is hardly the case. -Nicole Carr

You would think that Murray’s story would be widely known to schoolchildren and adults alike, although that is hardly the case. Only in recent years with the release of a new biography, a documentary and a U.S. Mint coin, have we begun to truly explore Murray’s legacy.

And until last week, there was recognition of the sum of Murray’s life on a federal government website.

But Murray’s page can no longer be found on the National Park Service website, and it ties to the other part of her legacy—the ways in which she grappled with her own identity and sexuality.

Murray’s sexuality and identity must be explored to understand her because they are the very things she admittedly struggled with throughout her life.

Murray often passed for and dressed as a man. She altered her given name-Anna Pauline- and opted for a gender-neutral name, “Pauli.” She sought the expertise of doctors and hoped that hormonal therapy could course correct what she was feeling deep inside-that she was trapped in a woman’s body.

In her journal she questioned whether she was "one of nature's experiments; a girl who should have been a boy."

While she was in relationships with women, she did not consider herself a lesbian. The National Museum of African American History and Culture notes that scholars recognize Murray would have been a transgender man today, but they continue to use she/her pronouns to describe her in keeping with the historical record.7

Last month and in line with a Trump Executive Order to supposedly “protect women” from gender ideology, federal government webmasters began erasing references to LGBTQ+. Information about trans and intersex people like Murray were also removed.8

Just days ago, the Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice condemned the federal government’s “efforts to erase Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray, and their invaluable contributions to our society, from the digital record.”

Built by Murray’s grandfather in 1898, the center is Murray’s Durham, N.C. childhood home. It’s an incubator for another generation of leaders.

The home is one the very few sites dedicated to the experiences of Black Americans in the National Register of Historic Places, making up just two percent of the catalogue.9

”The federal government has disabled at least one webpage, and scrubbed language related to Murray’s transgender and queer identities on others, on the National Park Service (NPS) website,” the statement read. “Murray’s legacy has been obscured alongside other figures and sites recognized by NPS, including the Stonewall National Monument, Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and others on a still-growing list.”

The center’s statement goes on to say, “Members of the LGBTQIA+ community have always been a part of the rich fabric of our society. Rev. Dr. Murray exists in a lineage of LGBTQIA+ Southerners who have advanced social justice work on a national scale, and whose contributions have gone on to shape history. Erasing this truth at the federal level censures American history and compromises the work of transgender and queer activists who stand in Murray’s wake today.”

You’ll often hear me say (as recently as last week during the State of the People address), that an assault on humanity needs a boogeyman to test our appetite for discrimination , hate, caste systems or the eradication of a people. Eradication can also include dismissal from the historical record.

The boogeyman has to scare you. It has to make you think your children are being attacked in school bathrooms or that there’s some massive show of transgender athletes competing against…well, anyone of the opposite biological sex . It leads to false data assumptions, outsized obsessions with other humans and fearmongering that codifies discrimination and misunderstandings into law.

During the era of mass lynching, the boogeyman was the Black brute-an oversexualized Negro who was after White women- or a “Nigger Lover” who deserved to hang like strange fruit from a tree as society sought “vigilante justice”

Surely, had Murray found the courage to ask or live aloud the questions of life that were reserved her personal journals and now the historical record, she would not have just been worried about modern day “Jane Crow treatment” in the schoolhouse or at the bus depot. She’d be worried about her ability to live in this society without being target practice for today’s policies or worse.

When we consider the complex lives of those who came before us, we should recognize their humanity and contributions to the greater good of society. Then we should refuse to allow their full lives to be erased from not only the digital record, but from the public memory that helps guide us through these perilous times.

No one can tell us how to live or lives or what to believe, but we should be committed to acknowledging, respecting and protecting one’s existence.

How will you combat erasure to fortify?

Tucker, E. (2022, May 17). Pauli Murray and Brown v. Board of Education. Teaching American History. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/blog/pauli-murray-and-brown-v-board-of-education/

(1939, January 26). Negro Applicant Lists Discussion Questions for N.C. “U” Students, California Eagle, 3.

(1940, March 27). Refused to Move, Fined. Richmond Times-Dispatch, 5.

Posted on February 16, 2022 By Kim. (2022, February 28). Pauli Murray: Changed history for Black People and Women - National Organization for Women. National Organization for Women -. https://now.org/blog/pauli-murray-changed-history-for-blacks-women/

About Pauli murray. About Pauli Murray | Pauli Murray College. (n.d.). https://paulimurray.yalecollege.yale.edu/subpage-2

The Pioneering Pauli Murray: Lawyer, Activist, Scholar and Priest | National Museum of African American History and Culture

Pauli Murray as a LGBTQ+ historical figure | National Museum of African American History and Culture. (n.d.-a). https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/pauli-murray-lgbtq-historical-figure

NBCUniversal News Group. (2025b, February 3). Government agencies scrub LGBTQ web pages and remove info about trans and intersex people. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-politics-and-policy/government-agencies-scrub-lgbtq-web-pages-remove-info-trans-intersex-p-rcna190519

About the center. Pauli Murray Center. (n.d.). https://www.paulimurraycenter.com/about-the-center

Share this post